Beardbrarian

How metadata can increase the visibility of the institutional repository

Wesley Teal, MLIS

Presented 11 August 2017 at Iowa State University Parks Library.

Available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 license.

Hello. I’m Wesley Teal. I am a candidate for the position of metadata librarian and I currently work as the Technical Services Supervisor at Wartburg College’s Vogel Library. Today I’ll be speaking about the ways metadata can help make institutional repositories and their resources more visible and discoverable.

The importance of institutional repositories

- Increased visibility of scholarship

- Increased citation for authors

- Increased scholarly collaboration and pace of research

- Increased prestige for institution

- Supports case for funding

- Increased citation for authors

- Democratize knowledge

- Increased control over scholarly output

- Support teaching

- Institution-level preservation

Institutional repositories play an important role in modern scholarship and scholarly communication.

Because institutional repositories are open, online, and searchable, unlike most traditional scholarly outlets, they can greatly increase the visibility of an institution's academic output.

This can lead to increased usage and citation of research. According to Jain et al., open-access articles are cited from between 50 percent to 250 percent more often than closed-access articles and online files receive more than 300 percent more citations than paper-only resources in some disciplines (4). A particularly striking example of how institutional repositories can increase research visibility can be seen by looking at Virginia Tech’s theses and dissertations collection. Susan Gibbons noted that in 1996, prior to implementing an institutional repository, Virginia Tech received an average of 175 interlibrary loan requests per month for theses and dissertations. In the 2002-2003 school year, those same theses and dissertations were accessed more than 7.3 million times through Virginia Tech’s institutional repository or more than 600,000 times per month (13). Here at Iowa State, electronic theses and dissertations in the institutional repository were downloaded more than 251,000 times between early September, 2014, and early May, 2015. Other resources in the repository were downloaded nearly 349,000 times during the same timespan (Thompson).

Making research openly available online also serves to increase the pace of scholarship and collaboration (Wesolek et al. 7). Valeria Aman notes that in the field of high energy physics 69 to 84 percent of preprint articles receive their first citation before being published via traditional means (76).

An institutional repository also serves as a showcase for an institution’s scholarly output, which can bolster an institution’s prestige (Crow 1) and encourage funding (3). Pekka Olsbo found that the relative citation impact of European universities tends to correlate with the relative openness of their research (89-91).

Because institutional repositories are open in nature, they can serve to democratize knowledge by freeing scholarly output from the narrow confines of publisher monopolies (Crow 3) and making it available to those who are not part of large research institutions and cannot afford subscriptions to academic journals and databases (Schlangen 3). By fostering an alternative, open publishing model, repositories allow and encourage institutions to take more control over their output.

Institutional repositories can support teaching by providing materials for classrooms, virtual teaching environments, and library catalogs (Jain et al. 3).

Finally, institutional repositories lifts the responsibility of preserving born-digital materials from their creators to the institution, helping to ensure that important research isn’t lost due to format obsolescence or hardware failure (Gibbons 11).

Institutional repository visibility issues

- Faculty don’t alway know their institution has an IR

- IRs and their holdings are not always discoverable by external systems

Although institutional repositories promise to drastically increase the visibility of scholarship, the reality at present doesn’t always meet that promise. A 2009 survey of universities in the United States and Canada found that less than 57 percent of faculty were aware that their university had a digital repository and that of those faculty that were aware, less than 10 percent had ever submitted their work to the repository (Tmava and Alemneh 856). Even where institutional repositories are well known among faculty, there may be little public awareness about them.

Fortunately, metadata can help.

Metadata to the rescue

- “A well-constructed repository with strong metadata is its own promotional tool for attracting content consumers, [Paul] Royster said”(Schlangen 6).

- “Although there are a number of contributing factors that affect digital resources visibility in IRs, it is the rich metadata that is consistently encoded that makes the digital items more discoverable” (Tmava and Alemneh 858).

While metadata serves many purposes, the most apparent and perhaps most important is to make materials discoverable. In Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions identified four general user tasks that bibliographic records, or, for our purposes, metadata should support. These are to help users find resources that match their search criteria, identify specific resources and distinguish them from resources with similar attributes, select the resource or resources that best suit their needs, and enable them to acquire or access the resource selected (IFLA 82). Each of these four tasks requires metadata that supports the visibility and discoverability of the resource described.

How metadata helps users

Good metadata helps users to

- find resources related to their search criteria,

- identify specific resources,

- select a resource appropriate to their needs,

- and obtain the resource they select (IFLA 82).

While metadata serves many purposes, the most apparent and perhaps most important is to make materials discoverable. In Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions identified four general user tasks that bibliographic records, or, for our purposes, metadata should support. These are to help users find resources that match their search criteria, identify specific resources and distinguish them from resources with similar attributes, select the resource or resources that best suit their needs, and enable them to acquire or access the resource selected (IFLA 82). Each of these four tasks requires metadata that supports the visibility and discoverability of the resource described.

Institutional repository searching

Rich, well-structured metadata allows

- Faceted searching

- Browsing

The most obvious way metadata can improve visibility is by enhancing searches within institutional repositories. Rich, detailed, well-structured metadata creates a broader discovery surface for objects and collections within the repository. Beyond title, author, and keywords, rich metadata can allow users to explore a repository by taking into account factors like resource type, creation date, location, subject, geography, related resources, and by collection, to name a few options. Envisioning the future of metadata and its role in discovery, Jennifer Bowen declared that “[m]etadata must support functionality to facilitate intuitive searching and navigation, such as faceted browsing and FRBR-informed results groupings” (12).

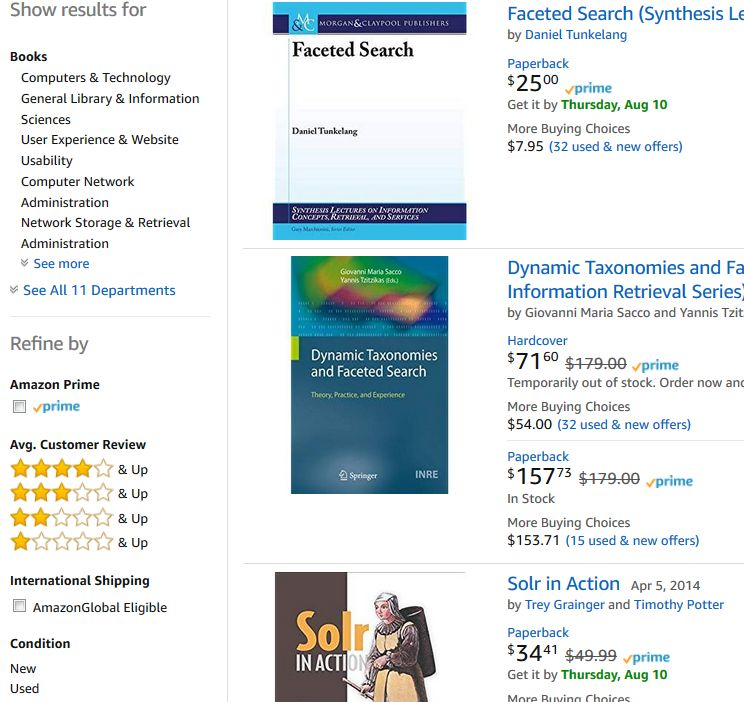

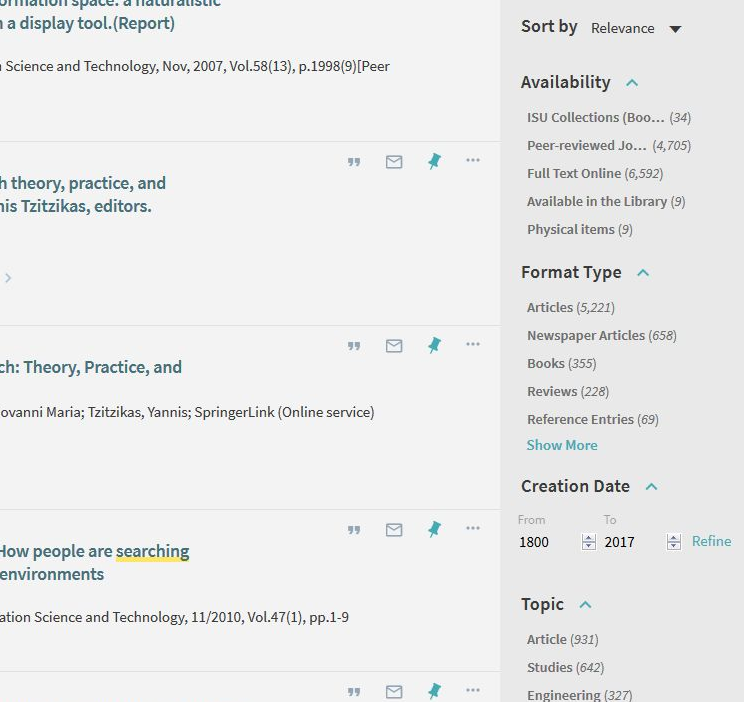

Rich metadata of the sort will be familiar to most academic and non-academic users, since they power the faceted searching capabilities of virtual all online retailers from Amazon to Zillow as well as most library catalogs. Users can filter by specific aspects as shown in the example from Amazon.com on the bottom left and from the university library’s catalog shown in the center.

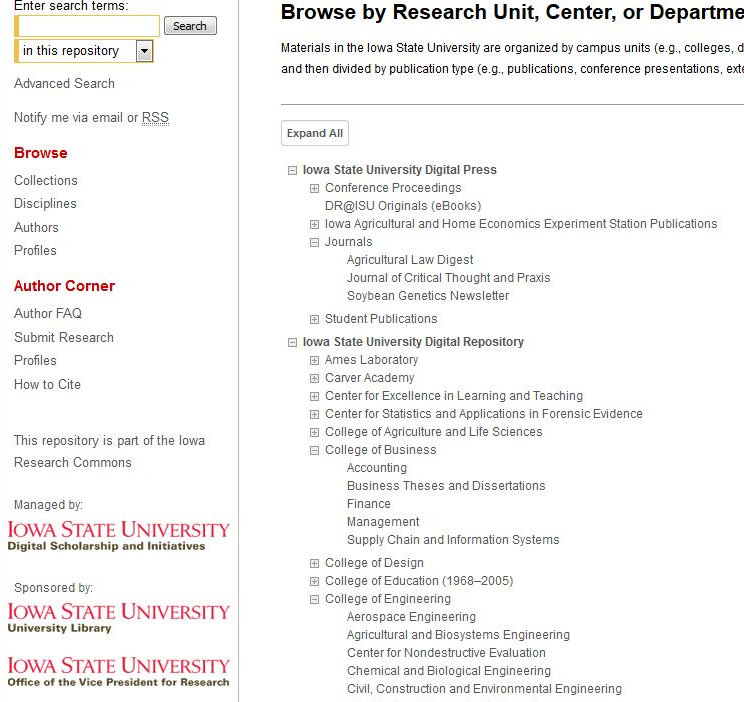

Well-structured metadata also allows users to browse collections based on various aspects, such as by discipline, author, or by exploring various levels of sub-collections as shown in the example from the Iowa State digital repository on the right.

One way to create rich, well-structured metadata is to use both collection-level and item-level metadata. Oksana L. Zavalina notes that employing both levels of metadata can increase retrieval rates of item-level metadata, provide context for resources, and improve the navigability of digital collections (2). She further asserts that the users she surveyed found structured, hyperlinked metadata, such as is typical in a faceted search or browsing user interface, preferable because such presentation was easy to scan and made it easy to find related resources (14).

Library catalogs and WorldCat

“The library catalog enhances access by virtue of being one of any library’s most authoritative and widely available resources. In addition, it is more familiar to many researchers than the institutional repository. The library catalog is also used by researchers worldwide, either directly or through WorldCat, and when the content it has catalogued is made openly available, such as through an institutional repository, those researchers may access it. Finally, harvesting and cross-walking institutional repository metadata in qualified Dublin Core to MARC also extends the function of the catalog to include non-traditional library materials” (Wesolek et al. 13).

Once the metadata exists in an institutional repository it can imported into the library catalog by way of crosswalking — or translating, the institutional repository’s metadata to MARC records, or other supported formats. From there it can be exported to WorldCat, creating two more access points for a repository’s resources via interfaces that are already familiar to regular library users.

Other institutional outlets

- Learning-management systems

- CMS

Institutional repository metadata also has the potential to be used with learning management systems such as Moodle, Blackboard, and Canvas. Sufficiently detailed metadata would make it easy to create course-specific collections that could then be linked to from an LMS. For systems where actual integration is possible, Bowen suggests that metadata could be integrated into learning management systems so that resources relevant to a specific course is automatically presented within the course page (12).

Bowen also proposes that metadata could be integrated into a content management system, specifically Drupal which includes features like a taxonomy system (11-12). Importing institutional repository metadata into the CMS that powers an institution’s website would allow repository items to be showcased and integrated into the institution’s public presentation with seamless ease.

Search engines

- General search engines, especially Google, account for the majority of researchers’ online information seeking.

- Institutional repositories are not always as visible to search engines as they should be.

To see how metadata can really increase the visibility of the institutional repository, however, we must look beyond the internal tools of the institution to the broader Web. Search engines such as Google, Bing, and Yahoo are now the primary way people discover information, even when conducting scholarly research. Arlitsch and O’Brien note that the vast majority of college students begin their research with a search engine rather than with a library catalog or similar resource (62-63). They note similar information-seeking behavior among faculty who make use of Google, Google Scholar, and Google Books in their research (63). This reliance on search engines can translate into heavy institutional repository usage. Clemson University’s digital repository receives two-thirds of its traffic from Google, Google Scholar, and other search engines (Wesolek et al. 9).

However, not all institutional repositories are as visible as they should be. Arlitsch and O’Brien found in 2010 that only 38 percent of the digital objects in the Mountain West Digital Library were discoverable via Google (64). In a 2013 survey, Petr Knoth found that only 27.6 percent of “research outputs” were linked to content that could be downloaded and indexed by the web crawlers that power search engines. He argues that this is due, in part, to inconsistently employed metadata and a lack of metadata that clearly identifies a resource’s technical attributes (2).

Ensuring interoperability

“For the repository to provide access to the broader research community, users outside the university must be able to find and retrieve information from the repository. Therefore, institutional repository systems must be able to support interoperability in order to provide access via multiple search engines and other discovery tools” (Crow 5).

In their Framework of Guidance for Building Good Digital Collections the National Information Standards Organization, or NISO, states that “Good metadata supports interoperability” (NISO 61). I’ve already shown some of the importance of interoperability in the way that metadata, once created can be reused across various institutional platforms. Insuring that a repository’s metadata is easy to reuse is even more important when it is being used beyond institutional control. As we’ve seen when institutional repository metadata is not interoperable with major search engines, it can limit the visibility of the repository’s collection.

One means to ensuring interoperability is to make sure a repository’s metadata unambiguously identifies resources so that search engine web crawlers can easily identify content and link it with appropriate metadata (Knoth 3). This is supported by Arlitsch and O’Brien who state that web crawlers that have trouble accessing a repository’s metadata can negatively impact discoverability in the search engine affected (64).

Another means is to always use the widely adopted Dublin Core schema to maximize ease of metadata harvesting, while optionally exposing your metadata in other formats as well (3). Bowen suggests that supporting the harvesting of multiple metadata schemas should be an important part of library discovery systems (9-10).

Another means for supporting interoperability is the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting, which is a “low-barrier mechanism for repository interoperability” (“Open”). The OAI-PMH uses Dublin Core as its base metadata schema, but allows for the use of additional schema (“FAQ”). While the protocol does not seem to have much traction among popular search engines, it is used by OCLC’s OAIster database which includes more than 50 million records harvested from more than 2,000 contributors (“OAIster”).

Search-engine-oriented metadata

- RDFa

- Microdata and Schema.org

- Supported by Google, Bing, Yahoo, and Yandex

- Used by more than 12 million websites

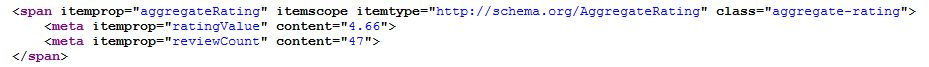

Perhaps the most effective means of making content more accessible to search engines is to translate metadata into the language of the web, by embedding it in the HTML pages that make up digital repositories. This is where the Resource Description Framework in Attributes, or RDFa, comes in. This recommendation, proposed by the World Wide Web Consortium, the standards body of the Web, lays out a framework for embedding structural and contextual metadata within standard HTML tags, providing valuable information that allow web crawlers and other programs to more precisely understand the nature and relationship of a page’s content (“RDFa”).

Building on the promise of RDFa, came Microdata, a simple specification for embedding metadata into web pages and Schema.org, a controlled vocabulary for use with the Microdata specification. The combination of Microdata and Schema.org provides a simple way for institutional repositories to “make their collections more discoverable and useful” (Ronallo) by offering another way to expose resources (Solodovnik 134). Additionally, the Schema.org vocabulary is supported by Google, Bing, Yahoo, and the Russian search engine Yandex (133). As of 2017, Schema.org was used to embed metadata on more than 12 million domains (Wallis et al.). This strong support by both content providers and content indexers like Google suggests a potentially enormous increase in visibility for institutional repositories that make use of Schema.org.

But making use of Microdata and the Schema.org vocabulary isn’t just about making resources more discoverable, it’s also about providing a rich means for search engines and other online entities to better display resources and to more accurately link them with related resources anywhere on the web.

Rich snippets

Jenn Riley notes that the “focus of Schema.org on the semantics of the text within Web pages helps take metadata processing on the Internet to a higher level” by encoding “small but vital bits of knowledge” into web pages, thus allowing search engines to not only index pages, but accumulate knowledge (21). One of the ways in which this accumulation of knowledge is used is through rich snippets, detailed results that include more than just a link title and a small snippet of text. By understanding the semantic meaning of a website, search engines can create detailed, well-structured, informative search results that are reported to lead to increased click-through rates (Ronallo).

As you can see in the example shown here, a page that makes good use of the Schema.org vocabulary allows for the automated creation of detailed results.

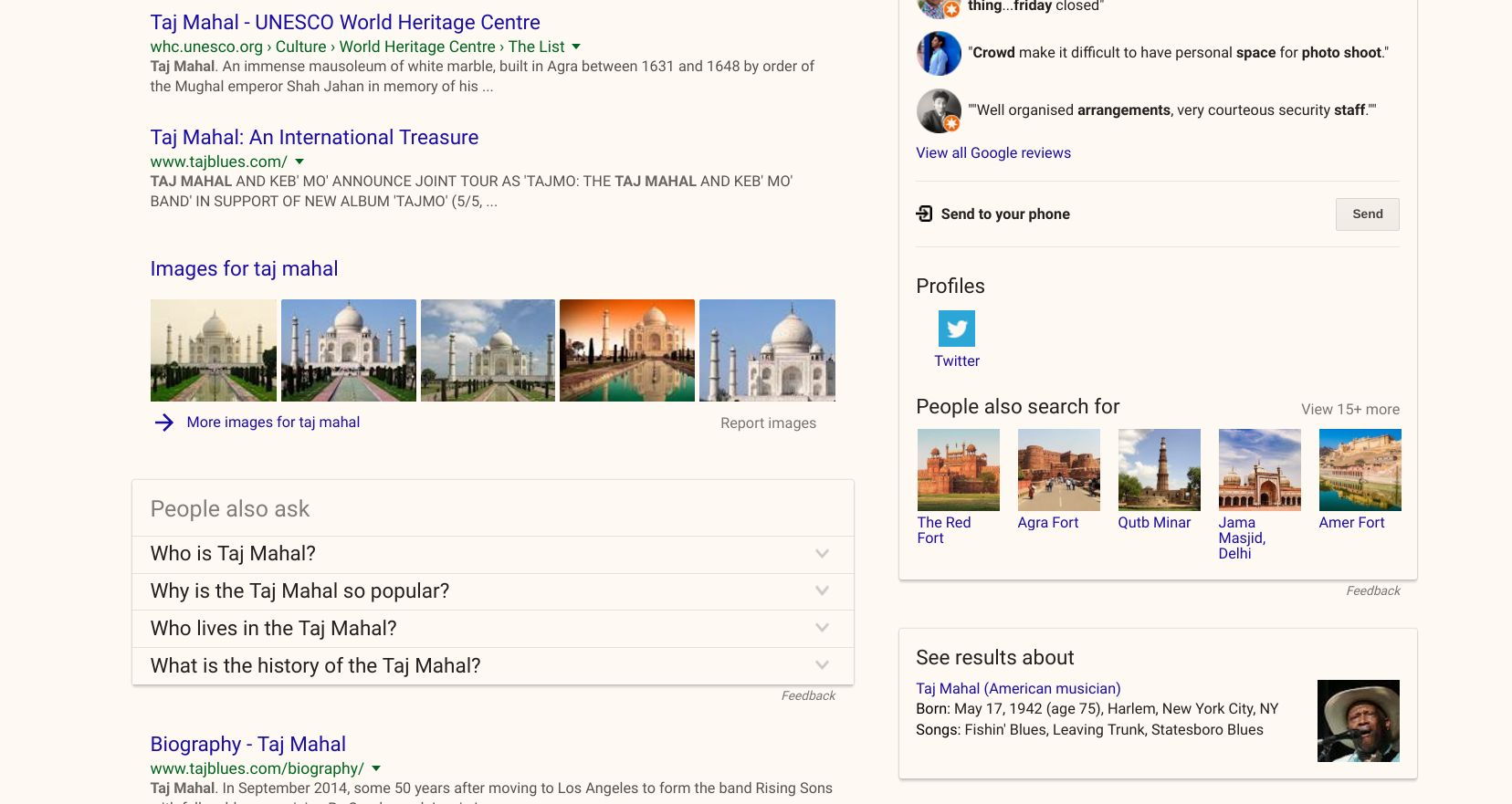

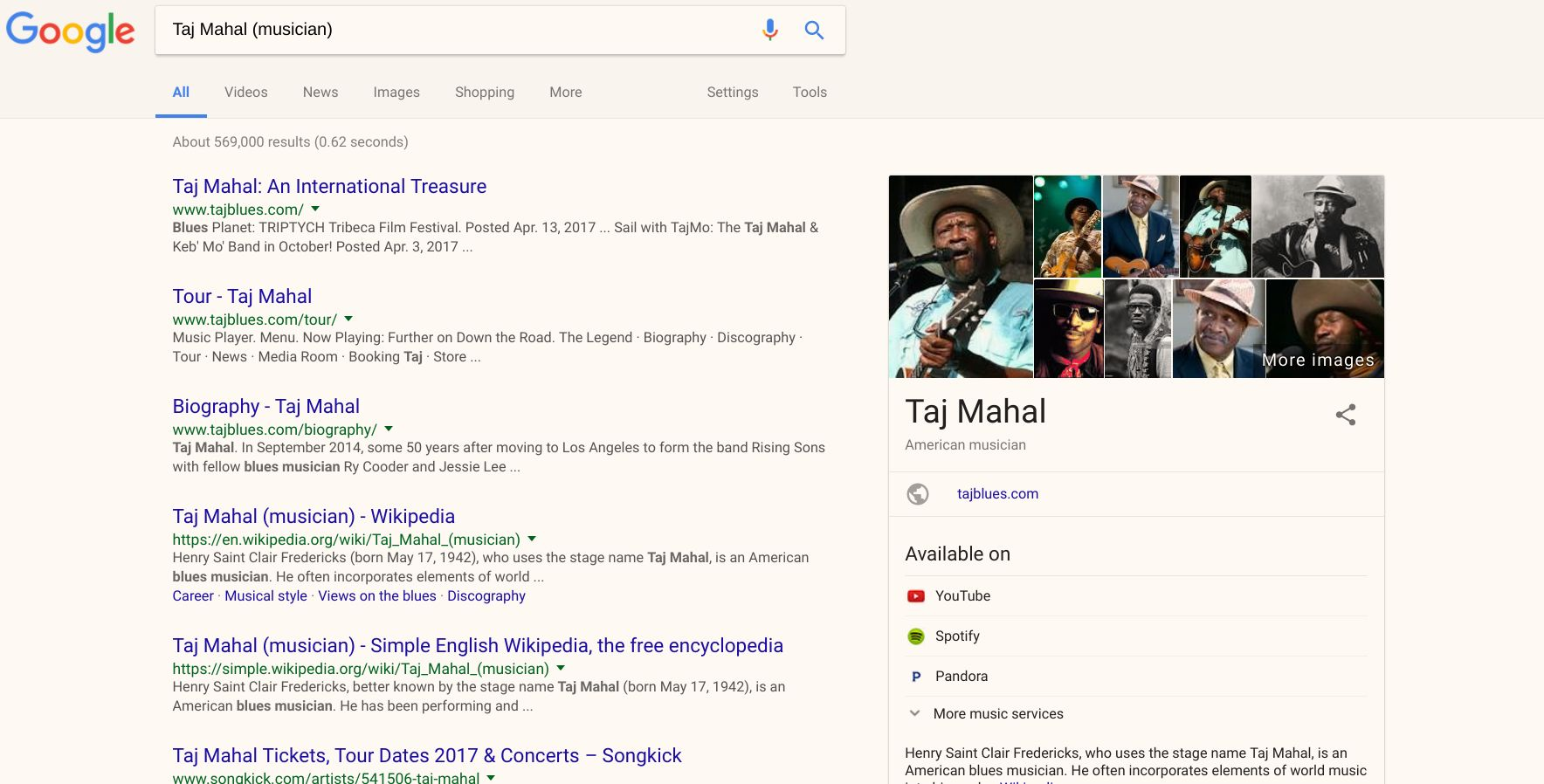

Google Knowledge Graph

Taking the potential of Schema.org to the next level, the Google Knowledge Graph proposes to allow Google users to search for “things, not strings” (Singhal). To this end, Amit Singhal described the ambiguity in search terms when announcing the debut of the Knowledge Graph by giving the example of the search term “taj mahal” which could refer to “one of the world’s most beautiful monuments, or a Grammy Award-winning musician, or possibly even a casino in Atlantic City, NJ. Or, depending on when you last ate, the nearest Indian restaurant.” As you can see in the examples here, Google is able to cluster related results, provide basic details about a topic, and offer suggestions for alternative topics, all thanks to rich, linked metadata.

By making the rich metadata from their digital repositories easily ingestible for web crawlers, institutions can help ensure that their online resources are linked to the appropriate object in the Google Knowledge Graph and other metadata-dependent search options.

Social media

“Metadata is at the core of social media platforms” (Riley 3).

To go one step further in embracing the metadata standards of the wider Web, institutional repositories can also embed Facebook- and Twitter-friendly metadata into their web pages, to allow for more visually-appealing and informative links when sharing repository resources on social media. Facebook employs the Open Graph Protocol to allow web pages to specify how their links are displayed on Facebook, including title, type, image, URL, and description, among other options (Allen).

As you can see in the example on the left, a link posted to Facebook from ISU’s institutional repository at the top, without Open Graph metadata, and one from A Book Apart, below, using Open Graph metadata happen to look fairly similar. However, the A Book Apart link displays what the website specified, while the repository link information had to be inferred by Facebook. Even where IR content displays reasonably well on Facebook, using Open Graph can allow institutions more control over how links are displayed, and may even be able to improve upon Facebook’s site scraping.

Twitter employs a similar metadata which it calls Cards to enable websites to richly display links (Allen). Of special note for institutional repositories, Twitter offers two kinds of summary cards as well as a player type that would allow audio and video resources hosted in the repository to be played directly on Twitter (“Card Types”). Twitter Cards use similar attributes to Facebook’s Open Graph and will fall back to using Open Graph if Card elements are missing (Allen).

In the example on the right, we can see that a link without Card metadata has less information and is less visually attention grabbing than a link with Card metadata.

Preservation

“Administrative metadata, which describes the technical characteristics of the digital file and any original physical source object, preservation actions, and relevant intellectual property rights and access permissions, is critical to the preservation of digital resources” (Otto 4).

A final, less obvious way that metadata helps make institutional repositories more visible is by aiding in preservation of items in the repository. If a resource is lost due to data corruption or it is embargoed because its usage rights are unknown, it cannot be visible to the public. By keeping appropriate administrative metadata, institutional repositories can help ensure the long-term visibility of their collections.

How metadata can increase the visibility of the institutional repository

- Improve navigability and discoverability within IRs

- Improve discoverability through other institutional resources

- Improve discoverability through search engines

- Improve the visibility of items shared via social media

- Help preserve resources for future use

In conclusion, metadata can increase the visibility of the institutional repository by improving navigability and discoverability within institutional repositories, improving discoverability through other institutional resources, improving discoverability through search engines, improving the visibility of items shared via social media, and helping to preserve resources for future use.

Work Cited

Allen, Ryan. “Improve Your Website’s Discoverability With Semantic Markup.” Envato Tuts+, 5 Mar 2015. webdesign.tutsplus.com/tutorials/improve-your-websites-discoverability-with-semantic-markup--cms-23223.

Aman, Valaria. The potential of preprints to accelerate scholarly communication: a bibliometric analysis based on selected journals. MA thesis, Humboldt University of Berlin, 2013. arXiv, arxiv.org/abs/1306.4856.

Arlitsch, Kenning and O’Brien, Patrick S. “Invisible institutional repositories: addressing the low indexing ratios of IRs in Google.” Library Hi Tech, vol. 30, no. 1, 2012, pp. 60-81. doi: 10.1108/07378831211213210.

Bowen, Jennifer. “Metadata to Support Next-Generation Library Resource Discovery: Lessons from the eXtensible Catalog, Phase 1.” Information Technologies and Libraries, vol. 27, no. 2, Jun 2008, pp. 6-19. UR Research, hdl.handle.net/1802/5757.

“Card Types.” Twitter Developer Documentation. dev.twitter.com/cards/types. Accessed 7 Aug. 2017.

Crow, Raym. “The Case for Institutional Repositories: A SPARC Position Paper.” ARL, no. 223, Aug 2002, pp. 1-7. SPARC, sparc.arl.org/resources/papers-guides/the-case-for-institutional-repositories.

Gibbons, Susan. “Benefits of an Institutional Repository.” Library Technology Reports, vol. 40, no. 4, Jul/Aug 2004, pp. 11-16. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=14019652&site=ehost-live.

IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records: final report. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, 1998. www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/frbr/frbr.pdf.

Jain, Priti, et al. “The Role of Institutional Repository in Digital Scholarly Communications.” [2009?]. www.ais.up.ac.za/digi/docs/jain_paper.pdf.

Knoth, Petr. “From Open Access Metadata to Open Access Content: Two Principles for Increased Visibility of Open Access Content.” Open Repositories 2013. 8-12 Jul 2013. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada.

National Information Standards Organization. A Framework of Guidance for Building Good Digital Collections. National Information Standards Organization, 2007.

Olsbo, Pekka. “Does openness and open access policy relate to the success of universities?” Information Services and Use, vol. 33, no. 2, 2013, pp. 87-91. doi:10.1002/tox.20155.

“Open Archives Initiative Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ).” Open Archives Initiative, 10 June 2002. www.openarchives.org/documents/FAQ.html. Accessed 2 Aug. 2017.

“Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting.” Open Archives Initiative. www.openarchives.org/pmh/. Accessed 2 Aug. 2017.

Otto, Jane Johnson. “Administrative Metadata for Long-Term Preservation and Management of Resources: A Survey of Current Practices in ARL Libraries.” Library Resources and Technical Services, vol. 53, no. 1, 2014, pp. 4-32. Proquest.

“RDFa 1.1 Primer - Third Edition.” W3C, 17 Mar 2015. www.w3.org/TR/rdfa-primer/.

Riley, Jenn. Understanding Metadata: What Is Metadata and what Is it for? National Information Standards Organization, 2017. www.niso.org/apps/group_public/download.php/17446/Understanding%20Metadata.pdf>.

Ronallo, Jason. “HTML5 Microdata and Schema.org.” Code4Lib, no. 16, 03 Feb. 2012. journal.code4lib.org/articles/6400.

Schlangen, Maureen E. “Content, Credibility, and Readership: Putting Your Institutional Repository on the Map.” Roesch Library Staff Publications, no. 1, 2015. ecommons.udayton.edu/roesch_staff_pub/1.

Singhal, Amit. “Introducing the Knowledge Graph: things, not strings.” Official Google Blog, 16 May 2012. googleblog.blogspot.com/2012/05/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not.html.

Solodovnik, Iryna. “Development of a metadata schema describing Institutional Repository content objects enhanced by ‘LODE-BD’ strategies.” JLIS.it, vol. 4, no. 2, July 2013, pp. 109-144. doi:10.4403/jlis.it-8792.

“The OAIster database.” OCLC. www.oclc.org/en/oaister.html. Accessed 2 Aug. 2017.

Thompson, Kelly J. “"Dissertation done: a recap of the ProQuest Electronic Theses & Dissertations Purchased Backfile Project, Phase 1.” Collections and Technical Services Conference Proceedings, Presentations and Posters, 19 May 2015. Ames, Iowa. lib.dr.iastate.edu/libcat_conf/2.

Tmava, Ahmet Meti and Alemneh, Daniel Gelaw. “Enhancing content visibility in institutional repositories: Overview of factors that affect digital resources discoverability.” iConference 2013 Proceedings, 2013, pp. 855-859. doi:10.9776/13437.

Wallis, Richard, et al. “Recommendations for the application of Schema.org to aggregated Cultural Heritage metadata to increase relevance and visibility to search engines: the case of Europeana.” Code4Lib, no. 36, 20 Apr 2017. journal.code4lib.org/articles/12330.

Wesolek, Andrew, et al. “Collaborate to Innovate: Expanding Access to Faculty Patents through the Institutional Repository and the Library Catalog.” [Clemson University Library] Publication, no. 101, 2015. tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pubs/101/.

Zavalina, Oksana L. “Contextual Metadata in Digital Aggregations: Application of Collection-Level Subject Metadata and its Role in User Interactions and Information Retrieval.” Journal of Library Metadata, vol. 11, no. 3/4, 2011, pp. 104-128. digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc77125/.